In order to understand these changes, you would have to be familiar with the PDQ rules as written. Of course, if you really couldn't care less and are just waiting for me to post some Jeff Dee super-hero art, then you can safely skip to the end of this post. Before I start on the rules-changes, I should mention that the transparency of PDQ, and the consequent ease of changing things around, is one of the bits I love about the system.

Okay, here we go. The two central ideas of these house-rules are:

- Ranks become synonymous with Modifier (MOD)

- MOD includes even numbers as well as odd.

So the first significant rules-change is:

1. New Ranks

[If that looks suspiciously like the spread from Marvel Super-Heroes, it's not a wild coincidence.]

2. Scale

Normal and Super-Scale don't perfectly overlap--once something drops below *Good, it is not super any more (the asterisk represents a Quality at Normal-scale).

3. Limited Ranks

Following from above, there are no Average-ranked Powers, as there are no Average-ranked Qualities.

4. Zeroing-Out

Occurs when a character actually zeroes-out; that is, when all Qualities and Powers are reduced to Average [+0]. No Qualities and Powers can be reduced below Average through conflict (the Poor and Feeble Ranks are only for purposes of Stunting).

[These three Rules all develop from one another. They come from my second continual confusion: although losing a conflict in PDQ is called "zeroing-out" it actually occurs when all Qualities have been reduced to less than 0 and then taking one additional hit.]

5. Fight

Every character has a Fight score. This is just the number of Ranks of damage he can take before zeroing-out. It's not so much a new stat as just formalizing and recording something implicit in the rules. Fight gives you a rough idea of how tough someone is. Most characters have 16 Fight (see No. 6 below), although the Intense Training Power can grant more (see No. 9 below).

[Once I realized that not all characters can absorb the same number of Ranks of Damage, I decided that it would handy to be able to assess a character's relative toughness at a glance. Fight ends up being something a bit like Hit Dice in Ye Auld Game: not an absolute measure of ability, but a good summary.

I waffled for a while on the name of this stat, with "Toughness" and "Resilience" as leading contenders for a while. But in a game that uses slangy terminology like "zero-out" and "being badass", I thought they were a bit too formal. Plus, I liked the idea of saying that someone "had all the fight knocked out of him".]

6. Character Generation

Characters begins with 10 Ranks (i.e. points of MOD) in Qualities and 6 Ranks in Powers. Remember from No. 3 above that the minimum Rank for a Quality or Power is Good [+1]

7. Weaknesses

Every character must have one Weakness, though he can have more. Weaknesses have two effects:

- Modify Dice: If dice are rolling and the Weakness applies, you have a functional total MOD of Weak [-2]. You also get 1 Hero Point.

- Modify Behaviour: If the GM thinks your Weakness would make you act differently, he may offer 1 Hero Point to change your behaviour. The player may decline. If the GM accepts that, then the player has to pay 1 Hero Point to exercise control. If GM wants though, he can up the ante by offering 2 Hero Points. The player may decline and GM must accept that, although player then must pay 2 Hero Points.

Vulnerabilities do not cost Ranks, but can be assigned any Rank desired. The higher the Rank chosen, the greater the effect and the greater the Hero Point award, which equals the Rank of the Vulnerability.

[Oddly and unlike Weaknesses, the rules as written do recognize Vulnerabilities as sources of Hero Points, but make the character pay for the privilege by using precious Ranks of Powers. I didn't care for that. Thinking purely economically (which many players do) a Vulnerability is an awfully expensive source of Hero Points that way.]

9. Intense Training

Each Rank in Intense Training is exchanged for 2 Ranks in Qualities. So someone who uses all 6 Power ranks in Intense Training gets 12 additional Ranks in Qualities. Note that this increases Fight score.

[The number of Ranks of Qualities granted by Intense Training was one of the first controversies I got involved in concerning T&J. The rules as written actually create a situation where there are more and less efficient character-builds (shudder) due to that artifact of Ranks not equaling MOD. To me, that's just entirely antithetical to the whole spirit of the game and this rule eliminates it.]

10. Spending Hero Points

An Upshift costs 1 Hero Point per Rank.

[Just because it costs 2 points as written per Rank which means 2 points per +2 MOD. So this just keeps the same scale and has the virtue of being easier to remember.]

11. Upshifts Beyond +6

Upshifting a MOD from +6 results in +1D+6. The additional die is rolled but only the highest two are retained. Additional Upshifts add more D6, but only the highest two are ever used.

[I find the PDQ rule that each Upshift beyond +6 adds another die to keep, really out of scale with the game. It also means that it is substantially more effective to Upshift a +6 Quality than any other and the benefits keep accruing. This new Rule means that there is a bit of diminishing return to piling on Upshifts which I prefer and keeps the result of the rolls all in scale.]

12. Spin-Off Stunts

Using a Power or Monstrous-rank Quality in a related but not clear-cut way i.e. expanding the penumbra of the Power/Quality. This includes using Offensive Powers for Defense and using Defensive Powers for Offensive. You can try it for free at -4 MOD from the base power or spend Hero Points for Upshifts.

[If you spot a trend toward consistency in these rules, it's not a wild coincidence. I'm not one of the old-schoolers who enjoys multiple, different systems for things. That's partly philosophical and partly because I can't be bothered to learn that many rules. Using offensive powers for defense (or the inverse) is a great touch in T&J and reminds me of one of the things I most loved about Villains & Vigilantes: virtually any power could be used for defensive purposes, even ones like Power Blast, although some powers (Force Field) were obviously more effective than others (Adaptation). V&V handled that with an ad hoc matrix, while T&J has a perfectly wonderful system to do it with stunting. Except that the rules as written don't use stunting for this purpose and make a new system just for this. Lazy me no like and changed.]

13. Signature Stunt

A Signature Stunt is a Spin-Off Stunt which you have done so many times that you have mastered it. It costs 1 Hero Point to use, but you perform at your base Power's MOD. In effect, you have permanently expanded the penumbra of your power for a minimal cost per use.

[Again about uniformity. The game already has a system for doing something super-cool in the form of Upshifting via Hero Points and doesn't need a second. Plus, the Rank/MOD inequality produces another weird artifact wherein it only really makes sense to Signature Stunt Powers at +6. It effectively acts as a very cheap method to boost already high-ranked Powers without doing anything for lower-ranked powers. This then plays into my issues with Upshifts (see No. 11 above)]

14. Shifting Stunt

This is a sort of middle ground between expanding the penumbra (Spin-Off Stunt) and improving an existing Power (Upshift). It functions mostly as described under "Shifty Business" on p. 55 of the T&J Book. A Shifting Stunt costs a flat 1 Hero Point and allows you to effectively Downshift one aspect of the Power while Upshifting another Aspect by a like amount. You may spend Hero Points to Upshift the Base Power before applying a Shifting Stunt.

[If you've been reading reading these commentaries so far, then I suspect that you already know why I changed this.]

15. Scale and Intensity

When helpful, Scale is applied to the Intensity Chart. Two common occurrences would be Weight (for lifting things) and Durability (for breaking things). Super-scale Ranks are denoted with an asterisk.

Lifting/Breaking something whose intensity is lower ranked than the one’s strength is an automatic action, unless conditions are applying Downshifts.

Lifting/Breaking something whose intensity is of equal or 1 Rank higher than one’s strength is a Complicated roll: roll 2D + relevant modifiers against the object’s TN.

A character can not lift/break something more than 1 rank greater in weight than his strength, except through the use of Hero Points.

[If this chart looks suspiciously like the one's from Marvel Super-Heroes...well, you know. The PDQ Intensity Chart is just fine for normal-scale games, but in a game that uses super-scale so much, it seemed helpful to have a super-scale chart. Plus, you know, this let's you play the "Who is Stronger: Hulk or Thing" game.]

16. Goons

The faceless mob of gangsters, soldiers, etc. They have 1 Quality: Good [+1] Goon. This means that they can be taken out by any successful attack. Super-scaled and Monstrous-Rank normal-scaled attacks upon Goons are Conflicts with each Damage Rank given taking out 1 Goon. This replaces the usual rule about Multiple Attacks (which only applies to better-than-Goons) meaning that the attacker need not take any Downshifts to fight a Goons Squad.

Goons can still team up on Heroes, though, so a horde of Goons can still be potentially dangerous. However, no more than 4 Goons can effectively fight one opponent at a time, so the highest MOD they can have to their attack roll is +4. Additional Goons form a separate Goon Squad for attacking purposes.

[Consistency again, plus trouble conceptualizing how T&J would accurately handle Spider-Man plunging into a mess of thugs and knocking out three or four at a go. The suggested method, making the fight a Complex situation and resolving it straight up or down seemed oddly undramatic to me.]

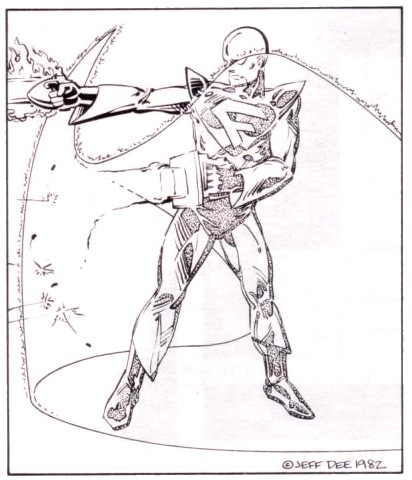

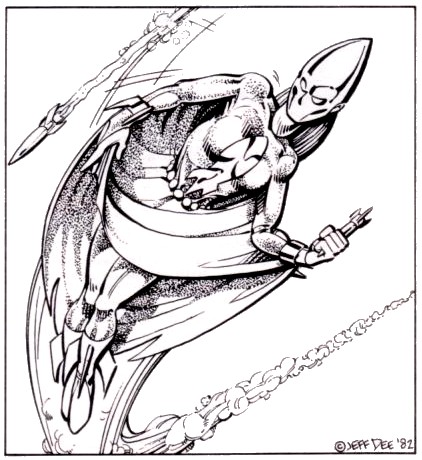

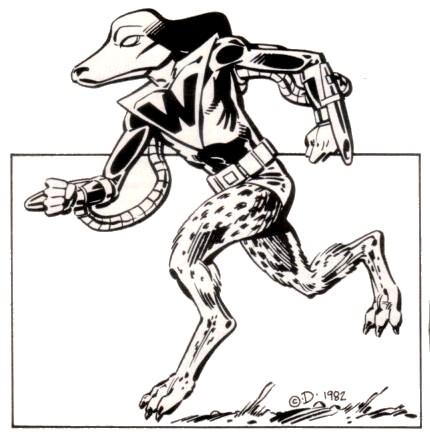

OK, there we go. A nicely formatted version of these rules is available at the old website if anyone wants them. Next issue: the Trotsky of Iron Men, the Fabulous F.I.S.T.!